|

|

The Opposition Takeover in al-Raqqa

On March 4, 2013, rebel groups overran government forces in al-Raqqa city, the first provincial capital and only urban center to fall to rebel hands since the start of the uprising.[1] Spearheaded by powerful Salafist groups, including Jabhat al-Wahdet al-Tahrir al-Islamiyya and Ahrar al-Sham, the offensive illustrates the growing strength of Islamists within the rebels’ ranks. The fall of al-Raqqa has reduced regime positions in eastern Syria to the military airbase outside Deir ez-Zour city and a handful of isolated outposts in northeastern Kurdish areas. As the regime’s reach continues to contract, al-Raqqa serves as an important test case for how the opposition will administer territory that they seize from Assad.

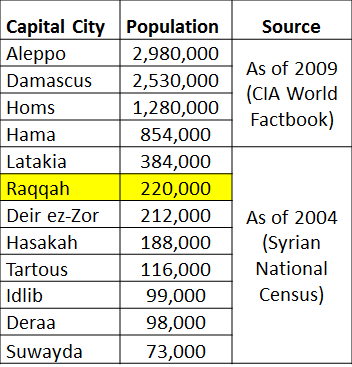

The significance of al-Raqqa city as a major population center should not be underestimated, despite the city’s relative isolation and remoteness. Before the current conflict, al-Raqqa was Syria’s 6th most populous city, with approximately 220,000 inhabitants, according to Syria’s 2004 census. Since the beginning of the conflict, al-Raqqa’s population more than tripled due to the arrival of internally displaced persons (IDPs), swelling to as many as 800,000.[2] Al-Raqqa has remained generally free from conflict, unlike the neighboring provinces of Aleppo, Deir ez-Zour and Hasakah, which has made it one of the few areas safe enough to absorb hundreds of thousands of IDPs.

One key reason why al-Raqqa has been relatively safe is that the historically pro-Assad tribal authorities in the province cooperated with the regime throughout the first two years of the uprising.[3] Assad saw these tribes as important allies, and even provided them with arms several months ago.[4] Because of these favorable tribal dynamics, Assad could afford to commit limited forces to al-Raqqa, namely the 93rd Brigade of the 17th Reserve Division, a historically ad hoc and under-resourced Syrian Army unit.[5] This economy of force mission was not capable of resisting a concerted rebel offensive. Rather, it was designed to show the flag and maintain law and order while relying on the allegiance of al-Raqqa’s tribes as the true basis of continued regime influence.

Once these tribal leaders began to see ties to Assad as a liability rather than an asset, Assad’s position in al-Raqqa crumbled rapidly. The rebels’ al-Raqqa campaign lasted less than a month between the February 11 surprise attack[6] on Tabqa Dam and the March 4 fall of the provincial capital. The fact that a statue of Hafiz al-Assad remained standing in a predominantly Sunni city until last week’s takeover is a testament to the traditional relationship between the regime and the tribal authorities. This also shows that rebel operations were relatively new to the area, and that the rebels overran the city much more quickly than other areas. Typically, opposition activity precedes rebel operations, and symbols of the regime are usually the first to be targeted and destroyed with statues of regime figures in cities disappearing long before falling into rebel hands.[7]

As the first Syrian city to fall under rebel control, al-Raqqa poses a major test for opposition governance. Since the rebels seized the city, they have posted guards at state buildings to prevent looting and destruction, returned bread prices to pre-war levels, and opened a hotline that residents can phone to report security issues.[8] Rebel groups are working closely with the local civilian councils to ensure the provision of basics such as food, water, and oil and are working with tribal authorities to maintain electricity and trash collection. They have also established sharia courts to mete out justice and provide a framework for transitional authority.[9]

Loyalists will watch these sharia courts closely and with apprehension to see how the opposition treats former pro-regime elements and minority populations in the city. A video posted after the rebels gained control showed al-Raqqa’s governor and the local Baath party leader praising Jabhat al-Wahdet al-Tahrir al-Islamiyya, the rebel group responsible for al-Raqqa’s capture.[10] Governor Hassan Saleh Jalali stated, “They are fair to those that seek their protection and they safeguard properties and defend civilians.”[11] The former loyalists showed no signs of physical injury, although their praise seems forced. Nevertheless, regime officials are reportedly being treated with care, and the captured political security officers and regime forces are being held in local prisons where they will await trial.[12]

On the other hand, several videos posted on YouTube show rebel groups capturing security forces, executing them in public squares, and dragging their dead bodies through the streets in images reminiscent of Qaddafi’s bloody demise. Rebel groups have also attacked several Shi‘a holy sites, including the bombing of the important Shi‘a shrine of Ammar ibn Yassir in northern al-Raqqa city.[13]

These conflicting accounts demonstrate the divisions that continue to hamper the development of the armed opposition and reveal the difficulties rebels face in attempting to govern. While many positive steps have been taken to ensure a level of stability and security for citizens, other actions have caused concern among the population who fear the presence of Islamist fighters in their city. Some residents of the northeastern city had pleaded with rebels not to enter al-Raqqa, fearing that Assad's war planes, artillery and missiles could target residential areas.[14] "The fear now is that the regime will [fire] SCUD missiles indiscriminately at al-Raqqa to punish the population," said Nawaf al-Ali, the al-Raqqa representative in the Syrian Opposition Coalition (SOC), an umbrella of the main opposition groups.[15]

Assad drastically ramped up his air campaign in order to ensure that the opposition cannot easily govern al-Raqqa. After only three airstrikes in all of 2012, the regime conducted five airstrikes in January 2013 and four in the first two weeks of February. After rebels seized Tabqa from loyalist troops in mid-February, regime airstrikes jumped up to twelve in the second half of the month, all centered on Tabqa (al-Tawrah on the map below). After rebels seized al-Raqqa in early March, the regime again conducted airstrikes on at least twelve occasions in the first two weeks of the month, this time centered on the provincial capital. This pattern of airstrikes demonstrates that the regime has primarily used airpower in retaliation for rebel victories rather than in defense of regime troops during the rebel offensive.

Until the fall of al-Raqqa, Assad had successfully prevented a rebel takeover in all of Syria’s major cities. Given the size of al-Raqqa’s population, this is a significant milestone for Syria’s opposition. Even so, the rebel capture of al-Raqqa is largely due to the shifting loyalty of tribal leaders and minimal Syrian military presence, rather than a rebel military victory per se. Al-Raqqah will test the efficacy of Assad’s strategy of displacing populations and denying rebel governance through air power alone. It will also test the rebels’ ability to govern. Their treatment of loyalist and minority populations will have significant implications for the prospect of limited ceasefires and political settlements in the future.

[1] “The opposition takes control of al-Raqqa,” al-Hayat, March 5, 2013. Translated from Arabic.

[2] http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/03/201334151942410812.html

[3] Rania Abouzeid, “Who will the tribes back in Syria’s civil war,” TIME, October 12, 2012.

[4] Sam Dagher, “Islamists try to tighten grip on Syria regions” Wall Street Journal, March 10, 2013.

[5] Joseph Holliday, "The Assad Regime: From Counterinsurgency to Civil War," Institute for the Study of War, March 2013. http://www.understandingwar.org/report/assad-regime.

[6] http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/02/11/us-syria-crisis-idUSBRE91A0MU20130211

[7] Matthew Barber, “The uprising and the new Syria: Islamists rise in Raqqa while Damascene Christians dodge fire,” Syria Comment, March 11, 2013.

[8] Ben Hubbard, “Captured Syrian city a test for rebel forces,” AP, March 10, 2013.

[9] “Rebels begin to govern in al-Raqqa,” Al-Jazeera, March 12, 2012. Translated from Arabic.

[10] “Inquiry of Raqqa Governor and branch head of the Baath party in Raqqa,” YouTube, posted on March 6, 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?&v=Weq3t6SJyfE

[11] “Inquiry of Raqqa Governor and branch head of the Baath party in Raqqa,” YouTube, posted on March 6, 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=Weq3t6SJyfE ; Sam Dagher, “Islamists try to tighten grip on Syria regions,” Wall Street Journal, March 10, 2013.

[12] Ben Hubbard, “Captured Syrian city a test for rebel forces,” AP, March 10, 2013.

[13] “Militants blow up Muslim shrine in Syria’s Raqqa,” Press TV, March 12, 2013.

[14] http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/04/us-syria-crisis-idUSBRE9230S620130304

[15] http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/04/us-syria-crisis-idUSBRE9230S620130304