|

|

Syria Update: The Fall of al-Qusayr

With the help of thousands of fighters from Hezbollah, Iran, and Iraq, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has achieved one of his most important military victories in the past two years by forcing the withdrawal of opposition forces from the town of al-Qusayr. The town is located in Homs province, an area central to the success of Assad’s overall military strategy. It is located along the southern route from Damascus through Homs province to the coast, at a juncture where regime forces have struggled to maintain their grasp. Rebel control of al-Qusayr had disrupted the regime’s critical ground line of supply from Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley and allowed for the cross-border movement of arms to rebels. Control of al-Qusayr now secures the regime’s line of communication from Damascus to the coast. Al-Qusayr now also cuts off access to cross-border weapons supplies to the rebels from Lebanon and provides an important staging ground for future efforts by the regime to retake the north and east.

The regime launched a major offensive against al-Qusayr in May 2013, culminating in the regime’s successful routing of rebel troops from the town in early June. The fall of al-Qusayr has thus effectively altered the balance of power on the ground and serves as a critical turning point in the civil war. With control of al-Qusayr, the regime can now strengthen its position in Homs province overall and better position itself to retake areas in the north and the east. Moreover, this regime success demonstrates the degree to which the conflict is no longer limited to Syria, but instead has engulfed the entire region, with troops from neighboring countries, including Lebanese Hezbollah in large numbers, reinforcing the regime's effort, and other regional and foreign fighters supporting the opposition. To this end, the engagement in al-Qusayr has escalated cross-border operations by both sides.

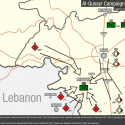

The regime has been fighting for control of Homs province since its major offensive in the city in February 2012. By early May 2012, following a U.N. brokered cease-fire, only sporadic street fighting and shelling occurred in Homs city and the surrounding area. During this time, the government controlled the majority of the city, with the opposition holding less than a fifth of Homs while fighting for control of a similar-sized area was still ongoing.[1] By mid-December 2012, the Syrian army had regained control of nearly all of the remaining portions of Homs city, except the Old City, Deir Baalba, and Khalidiya districts where rebels continued to hold out under the army’s siege. By the end of the month, government forces had recaptured Deir Baalba as well and were making significant inroads against the remaining rebel-held districts.[2] In March 2013, the Syrian government hoped to conclusively consolidate its control of the city and launched a major offensive into rebel-held territory.[3] However, thanks to opposition reinforcements that arrived from al-Qusayr, the rebels were able to push back government forces. By mid-March, they launched their own offensive into Bab Amr, attacking numerous government positions within the key district. Heavy fighting ensued.[4] Although it is uncertain how much of Bab Amr the rebels were able to recapture or continue to hold while under intense shelling by the Syrian regime, is was clear that government forces were struggling to maintain their positions and were at the risk of suffering major setbacks.

It was at this time in March 2013 that rebel commanders began reporting increasing numbers of Hezbollah troops in al-Qusayr. Although this was not a new phenomenon, the density of Hezbollah forces openly operating in conjunction with Syrian military forces was unprecedented. The border around al-Qusayr has never officially been settled, and many Shi‘a living in farming villages on the Syrian side of the border hold Lebanese passports. This had initially allowed Hezbollah to justify its activities in the area, and Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah early on claimed that those fighting near al-Qusayr were individual members of Hezbollah, acting of their own volition and not under party orders. But by October 2012, with the death of a senior commander near al-Qusayr it had become clear that Hezbollah was openly operating in the area under command and control of its leadership.

Since this time, Hezbollah’s involvement has shifted dramatically. By the end of March and early April 2013, Government forces were in danger of losing critical territory in Homs city. They were only able to hold on and push back against rebel forces due to the support of Hezbollah moving fully into the territory to fight on behalf of the Syrian government with entire units from the Bekaa Valley and Hermel mobilized. Hezbollah forces attacked rebel positions in and around al-Qusayr and reportedly committed a number of massacres in surrounding villages, forcing rebels to send reinforcements to al-Qusayr and stalling their offensive in Homs city. Hezbollah troops then squeezed rebel positions from the southwest, while the government regained territory in Homs city and pushed in on rebels from the northeast. Effectively, government forces and Hezbollah coordinated to place al-Qusayr under siege and isolate the rebels within the city.[5] Beginning in April, pro-regime forces managed to clear rebels from much of the countryside and isolate the town in order to prevent a rebel withdrawal. Once villages were secured, the surrounding area was subject to a build-up of government troops. Reinforcements for the fight were drawn from units in Daraa and Damascus. This strategy prevented the arrival of rebel reinforcements, which failed to find a way into the besieged town. The siege also barred the transfer of weapons to the area.

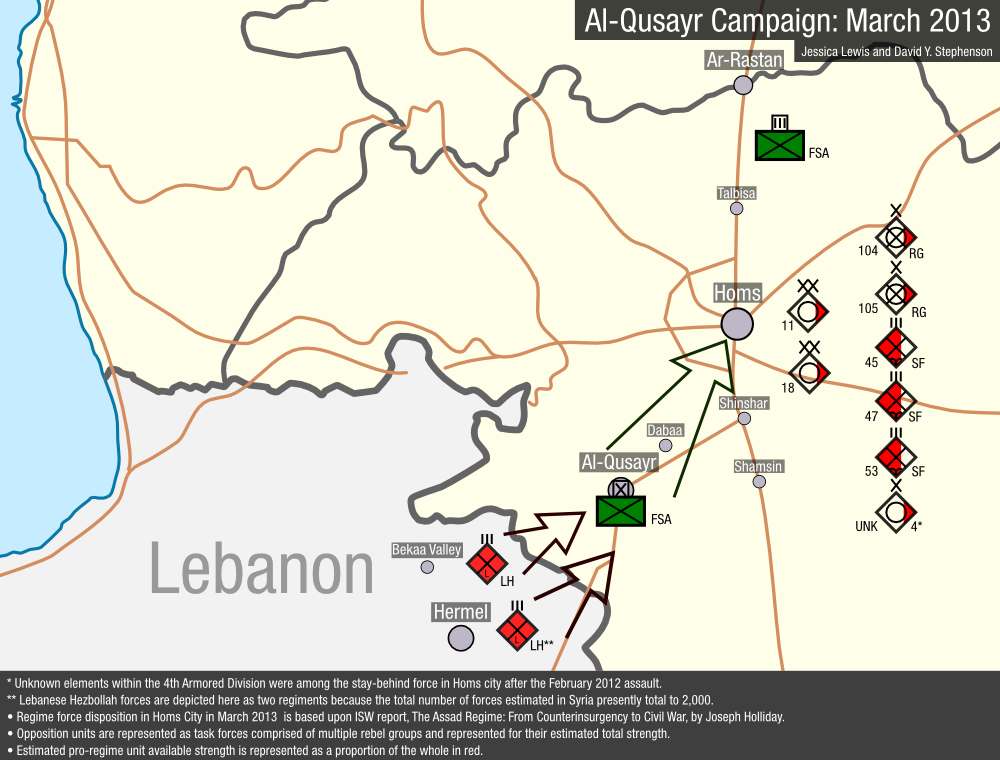

From this enhanced position, the regime launched a major offensive against al-Qusayr in early May 2013. In this offensive, regime troops combined with guerrilla detachments of Hezbollah and the militia-like National Defense Force. Government forces deployed artillery and airpower against the town, enabling bombardments that weakened rebel positions. Many rebels feared that they would be quickly defeated in the wake of the government offensive. One commander from the opposition al-Haqq Brigade stated, “If we hold our positions through the week it will be a miracle.”[6] Nearly twenty different opposition brigades came together to organize operations and repel the offensive, including the Farouq Brigades, the al-Haqq Brigade, the Mughaweer Battalion, the Wadi Brigades, the Qassioun Battalion, and the Ayman Battalion. Jabhat al-Nusra has also played a role, although their presence in al-Qusayr has largely been exaggerated in media reporting. In mid-May, it was reported that an important Jabhat al-Nusra commander, Abu Omar, had been killed along with a number of his subordinates.[7] It appears that other rebel groups benefited from the death of Abu Omar by asserting their own leadership, and Jabhat al-Nusra has since played a marginalized role in the fighting with other rebel groups taking the lead.

Initially, the rebels were able to hold their positions despite the relentless bombardment, and managed to push back Hezbollah troops who took heavy losses during the early stages of the offensive. The rebel’s success was partly due to a surge in weapons and resources that were smuggled into the town from Lebanon. Commanders from a variety of units were reportedly sending men into Lebanon to stock up on weapons before sending them back through Homs and into the remaining rebel-held neighborhoods before reaching al-Qusayr. Throughout May, the opposition groups in al-Qusayr were aided by a surge in reinforcements, with rebel groups from as far away as Aleppo and al-Raqqa sending forces to aid in the battle. These reinforcements amassed in areas around Rastan and Talbissa, two important rebel strongholds that have been used as launching points for attacks in Homs and al-Qusayr. Although these reinforcements were largely prevented from entering the town itself, they played a key role in targeting government convoys sending reinforcements and supplies to pro-regime forces.[8]

It was not until mid-May that their grasp began to slip on the city and, on May 19th, Syrian forces stormed al-Qusayr. Although media reports stated that Syrian forces had gained control of al-Qusayr’s city center and managed to retake all but ten percent of the city, rebel commanders denied the reports. Videos posted online confirmed that rebels continued to hold the city center and much of the northern areas of the city at that time.[9] Fighting continued unabated with both sides consolidating forces in and around the town through May. Rebel groups from across Syria sent units to bolster their defense of al-Qusayr, including the Tawhid Brigade from Aleppo, the Nasr Salahaddin Battalion from al-Raqqa, and the Usra Brigade from Deir al-Zour. In early June, video statements showed that at least some of these reinforcements had managed to enter the city and participate in clashes with regime troops.[10] On the government side, reinforcements from the 3rd and 4th Divisions and the Republican Guard were sent from Damascus to provide greater infantry support. Some Damascus activists described a lightened military presence in Damascus as regime troops were sent in greater numbers to al-Qusayr.[11]

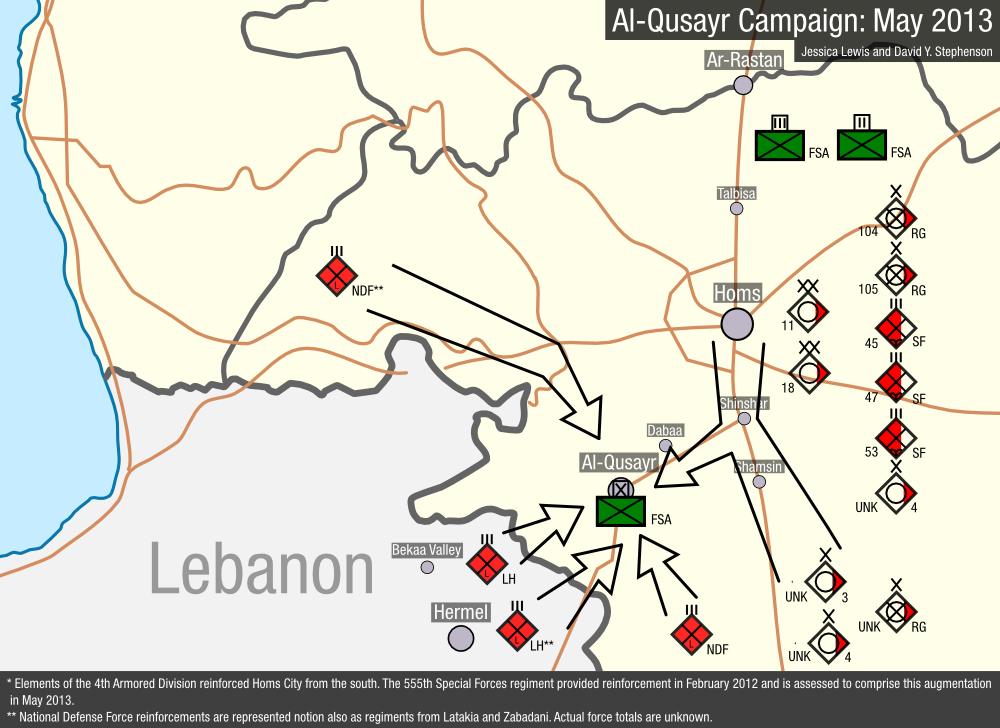

With the help of Hezbollah troops moving into Hamidiyah, the regime was able to retake the Dabaa military base and gain considerable ground in the southern section of the city by the end of May. From that time, the regime slowly advanced on rebel positions in the city and managed to cut off the majority of rebel supply lines. While conditions were dire for the armed opposition besieged in al-Qusayr, the rebels managed to maintain their positions in the western and northern sections of the city, as well as in key areas of the city center. They also managed to open an important corridor into the city near Shamsin from which they were able to attack government positions. The rebels proved to be well entrenched in al-Qusayr and aided through fortifications including tunnels.

On June 3, government forces heavily bombarded the rebel-controlled northern area of al-Qusayr, leveling row after row of buildings in order to deny rebels cover. Soon after, Hezbollah units carried out a ground assault against the remaining operational opposition forces. This combined attack proved to be the final assault necessary for the regime and Hezbollah forces to force a negotiated withdrawal of rebel fighters, who were running desperately low on weapons and ammunition. Opposition forces were allowed to withdraw from al-Qusayr along a narrow corridor of territory still under their control to reach the villages of Dabaa and Buwaydah al-Sharqiyah. While the Syrian government had formerly prevented the withdrawal of opposition fighters, a Lebanese-brokered agreement between opposition fighters and Hezbollah reportedly paved the way for a rebel withdrawal on the condition that opposition fighters be allowed to evacuate families and wounded people without being attacked.[12] However, fighting has again broken out in these areas along the northern edge of the town where opposition forces continue to retreat, and government forces have been conducting clearance operations to evict the remaining rebel forces.[13]

Although the regime success in al-Qusayr was quite slow, the well-coordinated offensive proved to be successful in defeating rebels in the town. The regime demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt its military tactics and strategically evolve in ways that made them much more effective against the insurgency. To add to this, Hezbollah’s efforts shifted the local balance of forces in the area. In combination with regular and irregular regime elements, Hezbollah's contribution remains a key contributor to the rebel defeat. Hezbollah has proven to be much more effective in confronting rebel forces as they have better experience in guerrilla tactics, unlike the ranks of Syria’s conventional army. To this end, Hezbollah has played a key role in the regime's development of effective irregular forces. It reportedly provides training and advice to local militia groups, Popular Committee elements, and the National Defense Army, all of which are playing a growing role in the regime's defense. Many rebel commanders reported that fighting Hezbollah troops was much more difficult than fighting against regime troops because “they are better fighters” and “more professional” than the Syrian army.[14] For his part, Assad acknowledged his debt to the movement, expressing “very high confidence, great satisfaction and appreciation toward Hezbollah” and promising to “give them everything.”[15]

Fighting in al-Qusayr revealed a new regime approach to fighting its insurgency. The Syrian government showed that it can use Hezbollah fighters, and possibly Iraqi and Iranian fighters, as a reliable infantry force alongside its own heavy weapons and airpower. The regime displayed a sophisticated level of operations which included heavy preparatory bombardment followed by the infiltration of irregular allied units, and finally armor-supported infantry attacks. The three phases of this strategy were jointly achieved through the coordination of separate chains of command, a difficult task under the best of circumstances. That the regime was able to cooperate so closely with Hezbollah leadership in combining regular, irregular, and allied units with separate functions speaks to the close nature of the relationship between the Syrian government and Hezbollah. The battle in al-Qusayr is unique in its proximity to Lebanon and the presence of so many Shi‘a Lebanese villages in the area, giving Hezbollah an edge in the fighting. Nevertheless, their increased involvement in battlefronts across Syria will be a critical boost to the regime. Over time, the replenishment of the regime's forces could allow Assad to rest and redeploy some of his forces for operations elsewhere in Syria, including efforts to retake certain rebel-held areas in the north and the east. This would give the regime renewed offensive and defensive capabilities and greater resources.

However, it should be noted that mobilizing militia units drawn primarily from Alawi and Shi‘a populations has its drawbacks. Command and control of these irregular forces will likely become increasingly difficult, and the Syrian government’s ability to control them may deteriorate over time. Already, the fact that Hezbollah helped negotiate a withdrawal despite the regime’s initial decision to prevent one suggests the likelihood of future disagreements over strategy and objective. Moreover, while there are clear short-term benefits, this mobilization also produces greater sectarian polarization and thus threatens the support Assad receives by critical portions of the Sunni community. This type of strategy was avoided by former president Hafez al-Assad who was clearly aware of the dangers of relying solely on minority groups. He was careful to downplay sectarian rhetoric and sought to build cross-sectarian patronage networks as part of the regime’s embedded authoritarianism, which ultimately contributed to the regime’s staying power. Losing Sunni support and relying on minority-drawn militias could put the regime in a vulnerable position, and it is unclear whether the government could then muster the manpower and support needed to reclaim lost territory.

As the conflict in Syria has protracted, the Assad regime has had time to reconsolidate and renew its offensive capability through an increased reliance on irregular forces and allied resources and support. This support from Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah has exceeded the amount of support going to the opposition, and has meant that the regime is far better resourced than its opponents. As the regime has adapted its strategy to match changing conditions, rebel forces have been unable to effectively respond. This is partly due to command and organizational issues that make it difficult to concentrate and coordinate significant forces, but it is also due to the lack of supplies, including much-needed ammunition, as well as their inability to withstand airpower. Overall, the opposition simply lacks the means for more effective resistance in the face of heavy bombardment by regime air power and artillery. This vulnerability was evident in al-Qusayr, where air power impeded resupply efforts and inflicted losses on opposition forces.

Although al-Qusayr may not be the decisive battle for Syria, it should be seen as an important turning point. By reasserting its military superiority in al-Qusayr, the regime has gained momentum, and through the help of Hezbollah and Iranian forces, it will likely be able to consolidate its control over the areas it now holds. This includes Syria’s most populated and economically important districts. Control of these areas will facilitate their advance on areas north of Homs province and possibly allow them to reclaim important rebel-held areas in the north and the east. Moreover, the regime victory effectively cuts off an important supply route to the rebels which will leave the armed opposition in an ever more weakened position. As for now, the regime does not have the forces required to move on from al-Qusayr and advance on other areas in the north. This means that the rebels have a brief window while the regime resets its capabilities. This window may permit them to develop a counteroffensive in order to disrupt the regime’s opportunity to capitalize upon its victory at al-Qusayr. However, the past performance of the armed opposition creates doubt over its ability to so. In light of the regime’s regained strategic and operational initiative, it will be even more difficult for the opposition moving forward.

This victory has also put the Syrian government in a better position as it enters the upcoming summit in Geneva. It is now able to transform its military advances into a stronger negotiating position, and there is now little pressure for Assad to bargain in good faith. His gains could even embolden Assad to push for all-out military victory rather than participate in the peace talks being promoted by the United States and Russia. This portends the failure of the summit and an end to international efforts to resolve the conflict through negotiations. If the international community truly seeks to enforce a negotiated settlement, they will have to do something to decisively change the balance of power on the ground ahead of the negotiations.

The battle for al-Qusayr symbolizes the conflict’s transformation into a regional imbroglio that can no longer be isolated within the Syrian context. Since the fall of the town, rebel fighters have already promised to take the fight to Hezbollah in Lebanon, launching over 18 rockets into Baalbek in a single day.[16] This has had a major impact on furthering sectarian polarization spilling over into Lebanon and Iraq, and exacerbating the role of identity politics and sectarianism in the region as a whole. While the defeat in al-Qusayr should not be seen as the decisive battle for Syria or as a forecast of regime victory, it does represent a new stage in the conflict through the open involvement of Hezbollah and Iranian forces at the side of the regime. That the regime was able to execute such an operation at this stage of the war testifies to its resilience and adaptability, and, more importantly, to the unswerving support of its allies Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah. The support of these countries will allow for Assad to continue his military onslaught, while the lack of a decision to reinforce the opposition with the necessary resources ensures the rebels’ inferiority on the battlefield and will ultimately result in the death of the Geneva negotiations.

[1] Lyse Doucet, “Homs: a scarred and divided city,” BBC, May 9, 2012.

[2] Alison Tahmizian Meuse, “Syrian troops hit Homs, kill 23 children,” The Australian, December 30, 2012.

[3] “Syria rebels capture northern Raqqa city,” Al-Jazeera, March 5, 2013.

[4] Syrian Observatory for Human Rights Facebook Page, March 10, 2013.

[5] Interviews with Syrian rebels conducted via Skype in March, April 2013 and in person in Istanbul in May 2013.

[6] Interview with commander of Liwa al-Haq in al-Qusayr, conducted via Skype on May 3, 2013.

[7] Jim Kouri, “Islamists suffer setback in Syria with killing of al-Qaeda linked leader,” The Examiner, May 22, 2013.

[8] Interviews with rebel commanders in May 2013.

[9] “Al-Qusayr, Homs, Colonel Abdel Jabaar al-Iqaydi,” YouTube, June 2, 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m2b6gRQ8_BI; interviews with commanders in May 2013.

[10] “Al-Qusayr, Homs, Colonel Abdel Jabaar al-Iqaydi;” interviews with commanders in May 2013.

[11] Interviews with Syrian commanders and activists in May 2013; Jeffrey White, “The Qusayr Rules: The Syrian Regime’s Changing Way of War,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, May 31, 2013.

[12] Saleh Hodaife, “Rebel withdrawal from al-Qusayr result of deal with Hezbollah,” NOW Lebanon, June 5, 2013.

[13] “Syria army deals severe blow to rebels in key town,” AP, June 5, 2013.

[14] Interviews with Syrian rebels conducted via Skype in March 2013.

[15] Liz Sly, “Assad forces gaining ground in Syria,” The Washington Post, May 11, 2013.

[16] “Syrian rockets hit Hezbollah stronghold in Lebanon, influential cleric fans sectarian flames,” AP, June 1, 2013.